Updated 4 November 2021 with Colin Cashin’s introduction

Shortly after Remembrance Day last year, I spent some time searching online for my grandfather William Gerald Phelan to see if any information was available about him. After sorting through various government sites I found Pierre’s blog about 420 Squadron, one of the two squadrons that he served with during his time with the RCAF. To my surprise and pleasure there were a few photos of him that I had never seen before. Over the next few days I spent hours going through the site reading about the history and missions, looking at photos and wondering about the people and the lives they lived.

My grandfather died in 1970 long before I was born, so we never got to meet. Most of what I know about him came from what my mom and other family members have told me. He studied philosophy in college, enjoyed singing in choir and playing the violin. He worked various sales-related jobs both before and after the war with cosmetics companies and at a car dealership. He liked playing sports like golf and hockey, and watching NHL games on television. Apart from facts and details like this, there isn’t much else I know. I get the impression the war took quite a toll on him, and his children only knew the person he was after returning from service.

It’s hard for me to imagine the sort of life he lived during this time period. Being stationed overseas with a wife and young child in Canada, not knowing if he would make it back, losing his younger brother Terence who didn’t return from a mission in February of 1945. Coming home and being expected to have a normal life, get a job, raise a family, all at a time when the diagnosis and treatment of war-related trauma was probably not very common. He never really talked about the war, but his experiences with the RCAF clearly stayed with him for many years after.

He had seven children, and just a few generations later his descendants number 61 and counting as great-grandchildren continue being born. Most of them live in Ontario where he spent most of his life, with others scattered coast to coast across Canada and elsewhere. It’s incredible to think that almost none of these people would exist had he not survived, if he had been sent on different missions on different nights. So many lives and family lines were cut short for those who were not so fortunate.

My family and I are incredibly grateful for the work Pierre has done with his blogs. They add a personal touch to the lives of people like my grandfather that does not exist in any government archives. These sites allow us to wonder about the human beings behind the names and dates, and what their experience during the war and life in general might have been like. I look forward to learning more about the details of my grandfather’s service as Pierre shares what he has been able to find out. Thanks to all the people who have shared the many fascinating and important photos, documents, and journals on these blogs. I hope they continue to serve as an important memorial and piece of history for interested readers, and descendants like myself who are lucky enough to find them.

Colin Cashin

Flying Officer William Gerald Phelan DFC

This was Flying Officer William Gerald Phelan’s citation I had found on airforce.ca website.

PHELAN, F/O William Gerald (J27718)

– Distinguished Flying Cross

– No.425 Squadron

– Award effective 19 September 1944 as per London Gazette of that date and AFRO 2274/44 dated 20 October 1944.

Born 7 February 1917 in Vancouver; home in Toronto; enlisted there 20 April 1942 and posted to No.1 Manning Depot.

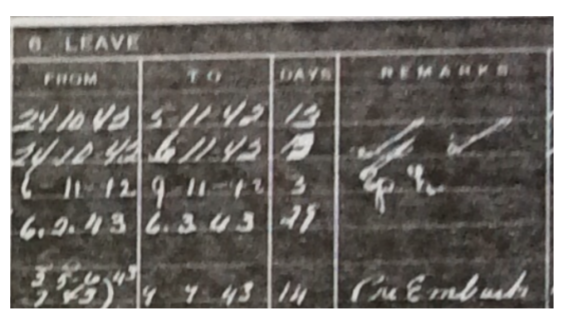

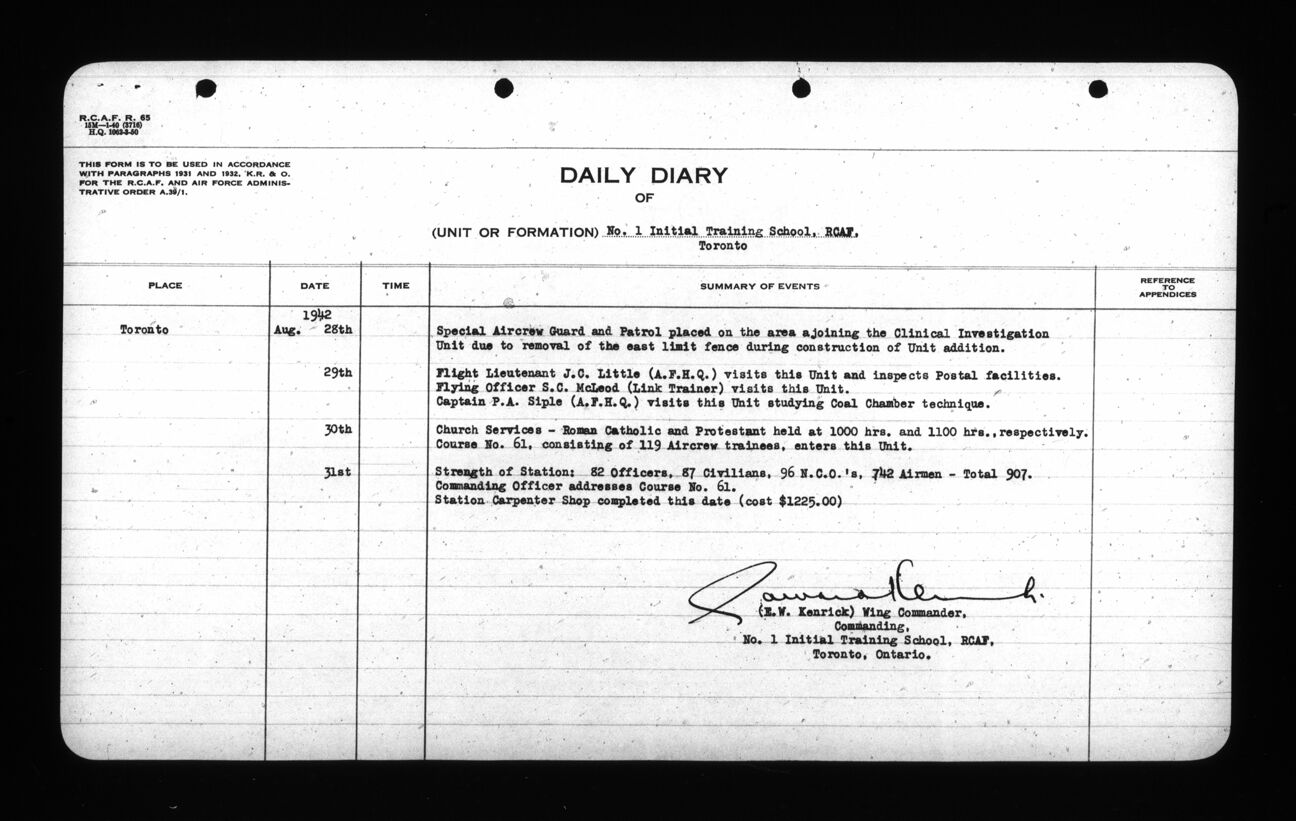

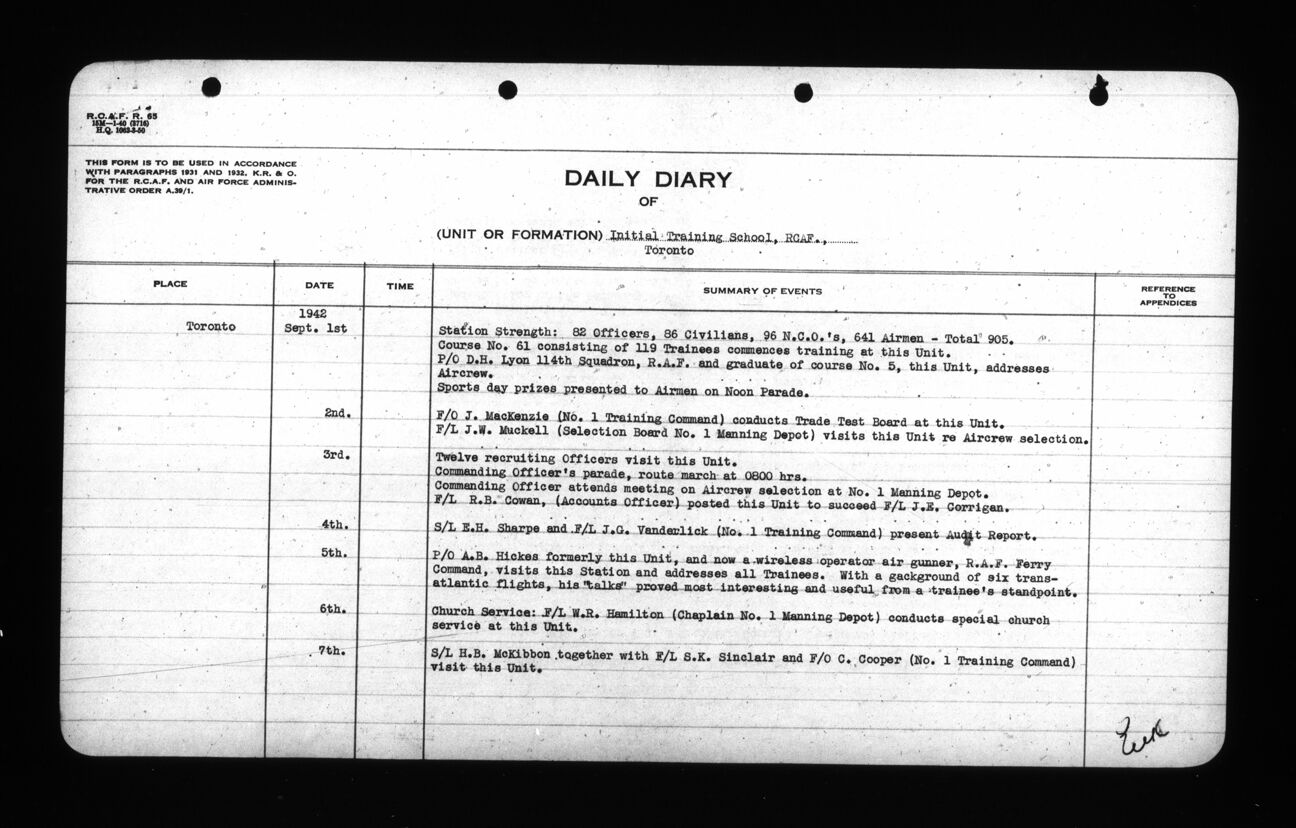

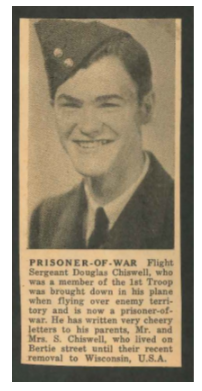

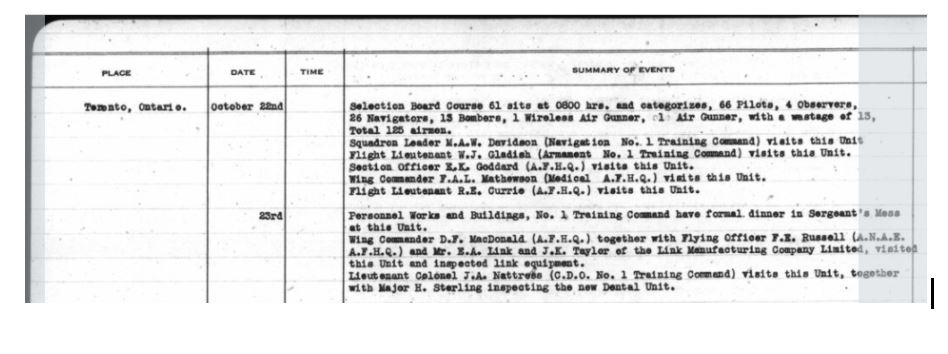

To No.1 ITS, 29 August 1942; graduated and promoted LAC, 23 October 1942 but not posted to No.9 EFTS until 21 November 1942; may have graduated 5 February 1943 but not posted to No.16 SFTS until 6 March 1943; graduated and commissioned 25 June 1943.

To “Y” Depot, 9 July 1943.

To United Kingdom, 15 July 1943.

Promoted Flying Officer, 25 December 1943.

Promoted Flight Lieutenant, 10 July 1944.

Promoted Squadron Leader, 5 August 1944.

Repatriated 2 September 1945.

Retired 17 October 1946.

Died 14 September 1970 as per DVA letter dated 23 October 1970. Medal presented at Buckingham Palace 29 June 1945.

RCAF photo PL-32718 (ex UK-14635 dated 13 September 1944) shows W/C Hugh Ledoux, recently appointed CO of No.425 Squadron, with two flight commanders – S/L Lionel Dupuis (left) and F/L Gerald Phelan (right).

Photo PL-33576 shows F/O W.G. Phelen (sic) (right) and F/L Real St. Amour.

RCAF photo PL-32755 (ex UK-14628 dated 9 September 1944) shows him alone.

Photo PL-41602 (ex UK-18125 dated 19 January 1945) shows commanders of No.420 Squadron – F/L F.S. McCarthy (Windsor, flight commander), W/C W.G. Phalen (sic) (Toronto, squadron commander) and S/L B.C. Motherwell (Vancouver, flight commander).

This officer has completed many sorties and has displayed exceptional skill and determination, qualities which were well in evidence when detailed for an attack one evening in July 1944. Early in the outward flight one of the engines became defective and had to be put out of action. In spite of this, Flying Officer Phelan was determined to complete the mission for which he had been detailed. Owing to the loss of air speed he knew that to follow the prescribed route would mean a late arrival over the target. He therefore altered course and, by the most direct route, went on to the target and executed a successful attack. On the return flight he skilfully controlled the use of the engines to conserve the petrol supply which had become much reduced and finally reached base. This officer has at all times displayed the highest standard of devotion to duty.

DHH file 181.009 D.1513 (Library and Archives Canada RG.24 vol.20600) has recommendation raised by W/C Lecomte, 26 July 1944 when he had completed 20 sorties (86 hours 30 minutes):

On the evening of July 6, 1944, Flying Officer Phelan was pilot of a Halifax bomber detailed to attack Coquereaux, France. Ten minutes after setting course from base, he discovered that the oil pressure in the starboard outer engine had become so low that there was no alternative to switching off the engine and feathering the propeller. With exceptional tenacity of purpose, he decided to continue to the target on the three engines. In order to maintain height it was necessary to change his petrol mixture from lean to rich. With the reduced airspeed it was difficult to reach the concentration point on time so Flying Officer Phelan, exercising unusual initiative, decided to fly a direct route instead of following the prescribed course. After encountering the main force of bombers he then put his aircraft into a gradual descent, thus maintaining the speed necessary to reach the target on schedule. Though the bombsight computer box was unserviceable, the target was bombed most successfully with the use of the sighting head. Continuing his magnificent display of airmanship, this officer brought his aircraft back to base despite the reduced petrol supply by again cutting off parts of the required tracks and by allowing a gradual loss of height.

Flying Officer Phelan’s initiative, skill and devotion to duty merit high praise. His fine offensive spirit and determination to complete his mission have been an inspiration to his crew. I recommend that his outstanding achievement be recognized by the immediate award of the Distinguished Flying Cross.

With that information I will be able to document more of Wing Commander Phelan’s career in the RCAF.

No.1 Manning Depot – 20 April 1942

No.1 Manning Depot – 20 April 1942

PDF version above

William Gerald Phelan enlisted in Toronto and he was then posted to No.1 Manning Depot. These are two images of No.1 Manning Depot in Toronto I once found on the Internet and that I posted on my blog about the BCATP.

Letter from Frank Sorensen to his parents who was there as a security guard.

Source

https://colinfranksorensen.wordpress.com/2019/10/20/chapter-two-march-26-1941-the-fourth-letter/

March 26, 1941

Security Guard Training

#1 Manning Depot, Toronto

Dear Mother & Dad;

Oh, I’m tired tonight, good and tired. I just came from a free show here in the building, it wasn’t much of a show hardly worth while seeing.

Get up at 6:00, make my bed, polish my boots and buttons, wash and go for breakfast. P.T. parade at 7:45 in fatigue clothes, we are marched outside and the Corp. chases us round the place. It’s just wonderful to have P.T. in weather 10 degrees above. One really has to work to keep warm. After P.T. we have squad drill until 11:30. Then I go to my bunk and rest a bit. I am a little tired especially my shoulders but the more it hurts the more I work with it. Tomorrow I don’t think I’ll feel anything. After dinner I have to be at another parade or route march at 1:30 and at 4:15 we are through for the day. I go to my bunk, rest, shine my buttons, I am awfully tired but after my daily shower I feel perfect. I shave twice a week. Supper at about 5:00, then I line up for my mail if any and I wish again that my name began with anything but S.

I go to my “home” again (bunk) play the banjo or I go to the lounge to write. I might also go for a walk along Lake Ontario – alone – believe me or not. You see, I realize now how expensive it is to fool about with women and what a lot of waste of time. Of course I wish I knew a real girl, but I’ve got plenty of time.

If I keep on spending money at the rate I am now I should be able to send ¾ of my money home. I’ll get $40 a month, $1.20 a day. It’s not much money, but I don’t see why I should spend it on food or anything of the kind when I get all the food I can eat (plenty of butter and apples). For the last week or so I have had 38 cents in my money belt and yesterday I spent the last bit as I missed my supper (because I have no watch). We’ll get paid next Monday for the first time. The $5 Dad gave me soon went on a money belt, boot polish, Brasso, etc. You don’t get everything in the army. It’s lights out now so goodnight.

Friday – I didn’t get my mail yesterday so I got your letter today. I was going to make this one a long letter but your letter reminded me that Dad was soon leaving so I’ll send it now. I just had my dinner and I have about ½ hour to get ready for the afternoon parade. I’m on what is called Security Guard Training which lasts for about 10 days so I won’t be here very long. The day Wilkins was in town we all marched down town. He stood on a platform as we marched past. In the evening we got free tickets to hear his speech and I went. As he was through he got up on the table and he nearly fell down. I went out before the others and stood in the front row as he got in the car.

Last week I went to “Lille Norge” and had a talk with them. They also take Danish subjects. I spent an evening with a fellow Nielsen. I must go.

Love Frank

There are several descriptions on the Internet on how life was for recruits at No. 1 Manning Depot in Toronto. Here’s one description that I once found which is not available anymore…

Training of Ground Crew Trades

The mightiest and most powerful air forces would soon find themselves short of serviceable aircraft if it were not for members of the ground crew who maintained, repaired and in their eyes “owned” the aircraft that the aircrews “borrowed”.

At Recruitment Centers across Canada the recruits for these trades were judged on their work backgrounds and aptitude tests. Although some knew what trades they wanted to be trained to from the very start others were steered into what was thought to suit them. And being in the military what you wanted and what you were best suited for was not always where you ended up.

Manning Depots

Once accepted and upon receiving orders by mail they headed to their Recruiting Office. From there they would be sent to one of the many Manning Depots around Canada. The two primary ones at the beginning being Brandon Manitoba and Toronto, with more added as the war went on.

For those lucky enough to be sent to Toronto it would provide them many great places to see and visit. If you could get a pass for the night, which was not all that freely given out from what my father wrote. And of course there were the lavish accommodations provided at No. 1 Manning Depot in the Canadian National Exhibition fair grounds namely the Equine Building or what most called the Horse building. Four to a stall and as my father wrote the horses had a better deal, they at least each got their own stall. My father had been a stable boy in his youth and many of the recruits were from rural towns and farms, to them it was familiar if not fully comfortable. To the city born recruits, even without there being many horses in the building, they found the accommodations more colourful and aromatic then they were used to.

Manning Depots took the civilian and, as my father wrote, ever so gently awakened them to the pleasures of military life. It was the place where you were given uniforms that didn’t fit and needles you didn’t want in places that were already aching from the last needle.

The new recruits were taught marching, saluting, personal grooming, hygiene and basically learning the ways of military life as the bottom peg in a system. For my father it was not completely new. His whole family had been Seaforth Highlanders for many generations.

Training for some of the newcomers was transferred abruptly from Toronto to Brandon. So my dad and a whole train load of recruits left sunny oh so warm Toronto late in the fall and arrived in the middle of a blizzard in Brandon with only their Summer dress uniforms to wear. Brandon didn’t have all the amenities of Toronto, but it didn’t matter. Passes were still just as stingingly handed out here as they had been in Toronto.

Here is another description…

To start with, they sent us to manning depot in Toronto, and we arrived there, and then, you know, you were allowed one suitcase when you left home, so you packed, you got into your best suit, best coat, best shoes, and all your best things were in the suitcase, and you went to Toronto and six of us from Saskatoon, went together. In manning depot, the manning depot was housed in the Toronto Exhibition grounds, in the various cattle barns and the horse barns. Well, the winter fair had just finished when we arrived, and I recall we were all lined up and a sergeant came out and said, “Okay,” he said, “First of all, how many of you here can ride a motorcycle?” So a number of eager chaps stepped out and they were marched off and we were marched off behind them in our suits, civilian clothing. They were all handed a wheelbarrow and we were handed pitchforks and shovels and brooms and we cleaned out the stables, the stalls in the horse barns.

Last description… and I guess you now get the picture…

Life at manning depot was strenuous, rigorous, and gave recruits their first introduction to military discipline and organization. Flight Lieutenant Asbaugh describes the daily regime of life at manning depot, which he remembers as being a shock to new recruits unused to military life:

Manning depot was quite a shock…It was our first introduction to the air force and military discipline…We were in the cow barn, in double-tiered bunks. There was just a mass of people in there…And we had drills and marching, and learnt to use the Ross rifle, and all that good stuff…The food was terrible; it was really shocking…They had some sort of arrangement with a caterer, and he could make the best rubber eggs you ever had in your life. The one thing that was really good about it was you got all the milk you could drink and all the bread and butter you wanted. The rest of the food was bad.

William Gerald Phelan enlisted in Toronto and he was then posted to No.1 Manning Depot. These are two images of No.1 Manning Depot in Toronto I once found on the Internet and that I posted on my blog about the BCATP.

Source

https://bcatp.wordpress.com/category/no-1-manning-depot/

There are several descriptions on the Internet on how life was for recruits at No. 1 Manning Depot in Toronto.

Here’s one description…

Training of Ground Crew Trades

The mightiest and most powerful air forces would soon find themselves short of serviceable aircraft if it were not for members of the ground crew who maintained, repaired and in their eyes “owned” the aircraft that the aircrews “borrowed”.

At Recruitment Centers across Canada the recruits for these trades were judged on their work backgrounds and aptitude tests. Although some knew what trades they wanted to be trained to from the very start others were steered into what was thought to suit them. And being in the military what you wanted and what you were best suited for was not always where you ended up.

Manning Depots

Once accepted and upon receiving orders by mail they headed to their Recruiting Office. From there they would be sent to one of the many Manning Depots around Canada. The two primary ones at the beginning being Brandon Manitoba and Toronto, with more added as the war went on.

For those lucky enough to be sent to Toronto it would provide them many great places to see and visit. If you could get a pass for the night, which was not all that freely given out from what my father wrote. And of course there were the lavish accommodations provided at No. 1 Manning Depot in the Canadian National Exhibition fair grounds namely the Equine Building or what most called the Horse building. Four to a stall and as my father wrote the horses had a better deal, they at least each got their own stall. My father had been a stable boy in his youth and many of the recruits were from rural towns and farms, to them it was familiar if not fully comfortable. To the city born recruits, even without there being many horses in the building, they found the accommodations more colourful and aromatic then they were used to.

Manning Depots took the civilian and, as my father wrote, ever so gently awakened them to the pleasures of military life. It was the place where you were given uniforms that didn’t fit and needles you didn’t want in places that were already aching from the last needle.

The new recruits were taught marching, saluting, personal grooming, hygiene and basically learning the ways of military life as the bottom peg in a system. For my father it was not completely new. His whole family had been Seaforth Highlanders for many generations.

Training for some of the newcomers was transferred abruptly from Toronto to Brandon. So my dad and a whole train load of recruits left sunny oh so warm Toronto late in the fall and arrived in the middle of a blizzard in Brandon with only their Summer dress uniforms to wear. Brandon didn’t have all the amenities of Toronto, but it didn’t matter. Passes were still just as stingingly handed out here as they had been in Toronto.

Here is another description…

To start with, they sent us to manning depot in Toronto, and we arrived there, and then, you know, you were allowed one suitcase when you left home, so you packed, you got into your best suit, best coat, best shoes, and all your best things were in the suitcase, and you went to Toronto and six of us from Saskatoon, went together. In manning depot, the manning depot was housed in the Toronto Exhibition grounds, in the various cattle barns and the horse barns. Well, the winter fair had just finished when we arrived, and I recall we were all lined up and a sergeant came out and said, “Okay,” he said, “First of all, how many of you here can ride a motorcycle?” So a number of eager chaps stepped out and they were marched off and we were marched off behind them in our suits, civilian clothing. They were all handed a wheelbarrow and we were handed pitchforks and shovels and brooms and we cleaned out the stables, the stalls in the horse barns.

Last description… and I guess you now get the picture…

Life at manning depot was strenuous, rigorous, and gave recruits their first introduction to military discipline and organization. Flight Lieutenant Asbaugh describes the daily regime of life at manning depot, which he remembers as being a shock to new recruits unused to military life:

Manning depot was quite a shock…It was our first introduction to the air force and military discipline…We were in the cow barn, in double-tiered bunks. There was just a mass of people in there…And we had drills and marching, and learnt to use the Ross rifle, and all that good stuff…The food was terrible; it was really shocking…They had some sort of arrangement with a caterer, and he could make the best rubber eggs you ever had in your life. The one thing that was really good about it was you got all the milk you could drink and all the bread and butter you wanted. The rest of the food was bad.

Next time…

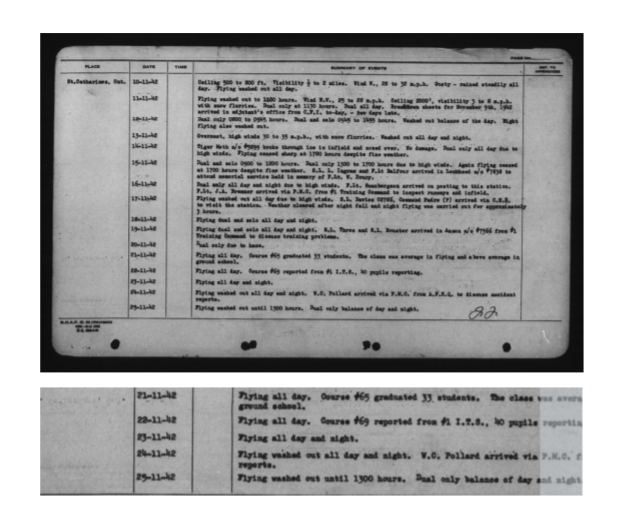

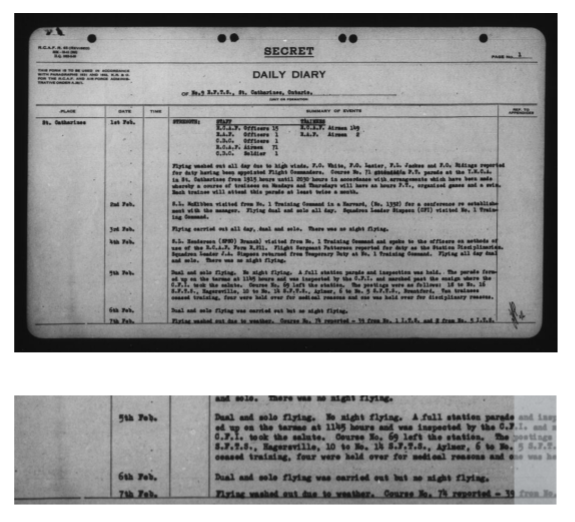

No.1 Initial Training School – 29 August 1942